Since starting this blog in November last year, I have discussed a number of gemstones and minerals from both a chemical/scientific point of view and from a lapidary point of view. Throughout many of these posts, I have referred to the 'Mohs Scale' or 'Mohs Scale of Mineral Hardness' when discussing the hardness of a given gemstone. As such, I thought it prudent to clarify what the 'Mohs Scale' actually is!

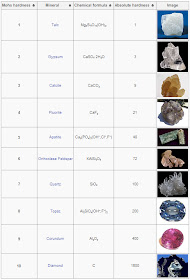

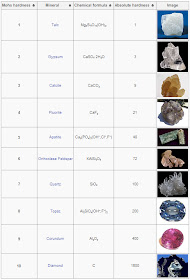

The Mohs Scale (also knowns as the Mohs Hardness Scale or Mohs Scale of Hardness) was developed by the German geologist Friedrich Mohs in 1812 and is widely used by lapidaries to describe the hardness of a given mineral or gemstone. Diamond was, at the time, the hardest material known to exist so is at the top of the list, with Talc being at the bottom.

Essentially what the Mohs scale does is describe the scratch resistance of a given material compared to other minerals. To simplify this, referring to the above table, gypsum will scratch talc therefor gypsum is harder than talc. Likewise corundum (sapphire, ruby etc) will be scratched by diamond so is therefor softer.

To find the Mohs classification of a particular gemstone or mineral one needs to find the softest material that will be scratched by the given gemstone, or find the hardest material that will be scratch by the given gemstone. The gemstone is then given a relative number.

To give an example of this, steel will (in general terms) scratch Fluorite, but will be scratched by Apatite, giving steel a Mohs rating of 4 - 4.5

The scale does not refer to the relative hardness of a given material, ie. Corundum is twice as hard as Topaz, but diamond is 4 times harder than corundum. The table below (courtesy of

Wikipedia) shows this with the additional column titled 'Abosulte Hardness'.

|

Mohs Hardness Scale with additional column

titled 'Absolute Hardness' |

So from now on, when I refer to the 'Mohs Hardness Scale' when discussing gemstones, you will know what I am on about!

And if you like the content of this blog, feel free to share!

Until next time!

.jpg)

.jpg)